Turkey and the Backpack Bombs

Turkey’s unfulfilled—and ultimately unnecessary—quest to defend itself from Soviet attack with man-portable nuclear munitions.

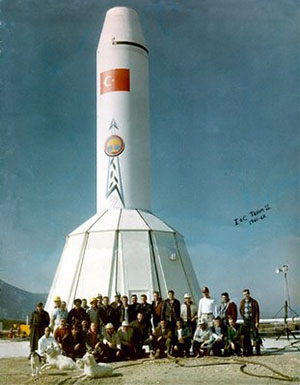

A Jupiter medium-range ballistic missile emblazoned

with a mushroom cloud and the Turkish flag, circa 1962.

Source: allempires.com

Last week, Foreign Policy published a fascinating article by Adam Rawnsley and David Brown documenting the hidden history of US Cold-War era plans to use man-portable Special Atomic Demolition Munitions (SADMs) to combat Soviet forces on battlefields in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. The lightweight, low-yield “backpack” nuke was intended to counteract the Warsaw Pact’s presumptive conventional military advantage and to reassure wary allies of the US commitment to use nuclear weapons to defend them.

The Turkish Republic never felt completely comfortable with US and NATO external security guarantees. During the Cold War, Ankara sought the deployment of nuclear weapons as physical symbols of the West’s commitment to its defense, a critical tool for NATO security and burden sharing, and a vital link to the United States. Turkish policy makers worried that in a crisis, Washington would fail to honor its commitment to defend Turkey with nuclear weapons, lest such use prompted the Soviet Union to strike the US homeland.

Initially, Ankara did not express any particular discomfort with the necessary dual-key nuclear arrangement (whereby any use of nuclear weapons stationed in Turkey required US authorization). In fact, on September 10, 1959, Fatin Rustu Zorlu, Turkey’s minister of foreign affairs, was so eager to conclude a bilateral basing agreement with the United States that he prodded his American counterparts to finalize the arrangement before his trip to the UN General Assembly on September 19. The United States complied, and on September 16, Turkey accepted the US – drafted agreement without making any changes to the text. [1]

Within a few years, however, Turkey’s doubts about the strength of the US commitment grew with several subsequent events: the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, President Lyndon Johnson’s stark admonition against Turkish military intervention in Cyprus—the “1964 Johnson letter”—and the phasing out of the “massive retaliation” nuclear war plan in favor of the “flexible response” nuclear doctrine.[2] In particular, the US decision to withdraw medium-range Jupiter missiles from Turkey only a year or so after they were deployed— partly in exchange for the Soviet withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Cuba —was deemed to be an affront to the nation’s dignity.[3] In 1967, Ankara sought to lessen the time needed to detonate nuclear weapons on its soil. The Turkish military presented a plan to the NATO Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) that called for the United States to predelegate control over Atomic Demolition Munitions (ADMs) to the Turkish General Staff. The Turkish military was concerned that NATO would fail to authorize the use of nuclear weapons on Turkish territory before Ankara’s forces were overrun and Soviet forces successfully occupied large swaths of the country.

The United States was concerned about the Turkish request, but then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was happy that NATO ministers had “done their homework” and had not wasted time at the meeting with “long prepared speeches.” [4] McNamara had grown concerned that the allies lacked a coherent plan to use the 7,000 nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and that this eroded Alliance deterrence. Thus, at a NATO NPG meeting in Ankara in September 1967, he prodded the allies to come up with more “concrete operational plans for specific nuclear weapons in defined contingencies and geographical areas.” [5]

The ADM issue, however, remained complicated. While the United States had debated the merits of forward deploying ADMs at NATO bases in Europe, many of its allies were opposed to the idea of hosting nuclear weapons that could only be used on one’s own territory.

Turkey Makes Its Case

Ankara had no such concerns. Before the September 1967 NPG meeting in Ankara, Ahmet Topaloglu, then – Turkish defense minister, worked with US strategists to devise a plan to use ADMs in the mountainous regions on Turkey’s eastern borders. However, the decision to permit Turkey to present its plan to the NPG posed a problem for the United States.

According to Seymour Weiss, then a special assistant to the secretary of state, “The Turks are known to be the strongest advocates of predelegation … this is understandably so because without predelegation time delays in receiving permission to use nuclear weapons would result in Turkish forces being overrun … .” [6] Turkey’s position on predelegation was so strong that it affected its view of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). While Turkey was in substantial agreement with the NPT, Ankara expressed interest in receiving an adequate security guarantee, and inquired whether the treaty would permit the United States to predelegate the authority to use nuclear weapons to the Turkish military. [7] Turkey signed the NPT in 1969, but did not ratify the agreement until November 28, 1979, a decision it agreed to take two years earlier in order to allow European assistance on the construction of a nuclear technology center. [8]

The United States appears to have dismissed Turkey’s fears regarding the time needed to authorize the dispersal and detonation of ADMs. Weiss noted that “because of these Turkish views and because we believe that their knowledge is not highly sophisticated, we have asked the Turks to present a dry-run of their briefing to the NPG Deputies in advance of NPG meeting; and we have offered to provide them with assistance in preparing their briefing.” [9]

The plan was finalized on January 15, 1968. It called for the forward deployment of seventy-two ADMs in Turkey. Ankara had hoped to pre-position twenty-nine weapons in the expected force area and ring its defensive position with another thirty low-yield ADMs. Ankara reasoned that the lower-yield weapons would help reduce the risk to Turkish troops operating in the area. The other thirteen weapons were to be held in reserve. [10] Mission planners had concluded that eastern Turkey was “ideally suited for ADM employment,” but acknowledged the risk of fallout to civilians in the area, should an invasion come with little or no warning.

NATO updated its political guidelines for the use of nuclear weapons in December 1969. The updated rules did not include the forward deployment of ADMs in Turkey, but promised that NATO would shorten the time necessary to agree on the use of nuclear weapons in appropriate geographical areas to prevent Soviet forces from overrunning Turkish defenses.

In the end, the United States never deployed ADMs in Turkey, and chose instead to keep them stored with the 66th ADM engineers, who had been based out of Vicenza, Italy, since 1956. Ankara was disappointed: as in the case of the Jupiter missiles, Ankara viewed ADMs as both a critical tool to prevent invasion and as a symbol of the US commitment to Turkey’s defense.

A Lingering Legacy

As part of its plan to use ADMs, the United States made preparations to support the special forces units tasked with parachuting behind enemy lines to deliver and detonate ADMs. Rawnsley and Brown write, “If the Green Light teams were lucky enough to be alive after the weapon detonated … [they] could seek out weapons and supply caches hidden across Eastern Europe and marked on special maps.” These secret arms caches continue to play a central role in Turkish politics, albeit in a far different way than NATO mission planners originally intended.

These arms caches and specially trained forces trained to “stay behind” and sabotage Warsaw Pact forces in the event of an invasion have since been linked to elements of the so-called “Turkish deep state,” which is purported to consist of shadowy groups working with elements in the bureaucracy, armed forces, intelligence services, and the mafia to carry out state sanctioned ethnic cleansing in Kurdish areas during the 1990s. And, after a 2007 raid in Istanbul, the deep state is alleged to have been part of an effort to foment civil unrest in Turkey to help instigate a military coup.

Yet, as Rawnsley and Brown note, “the backpack nuke” and the associated arms caches are “perhaps the most darkly comic manifestation of an age struggling to deal with the all-too-real prospect of Armageddon.” The ADM battle plan, for example, helps shed some light on the numbers of nuclear weapons slated for use against Soviet targets in and around Turkey during the Cold War.

A Multitude of Targets

As of 1978, for example, Turkey hosted nuclear warheads for the Honest John surface-to-surface rocket, B61 nuclear gravity bombs, and nuclear artillery shells. While the battle plan remains classified, in the event of war Turkish aircraft were expected to target Soviet oil resources in Romania, Azerbaijan, and the Caucasus. The Turkish forces were then expected to fall back gradually to the Hatay region, where they would then make a final stand in the Iskenderun area in southern Turkey, near the Syrian border. From there, Turkish forces could then attempt to block a Soviet invasion of the Middle East and thereby allow the Alliance to maintain access to Middle Eastern oil fields. [11]

Thus, it is not too far of a leap to think that Turkish aircraft, armed with US nuclear weapons, could have been ordered to target installations in areas ranging from Baku to Moscow, and Hatay to Thrace. In addition, short-range nuclear artillery shells, would likely have been used to slow down and destroy Soviet/Warsaw Pact forces along invasion routes on Turkey’s eastern and western borders.

Ankara, therefore, need not have ever worried about its forces being overrun before the use of nuclear weapons was authorized, or the necessity of stay-behind groups working to sabotage Soviet forces. If one simply examines likely Soviet targets in Turkey—airfields, NATO military bases, Turkish military bases, etc.—and combines those with the expected places where NATO nuclear weapons would have been used (the Bulgarian border, eastern borders, along the Black Sea), it is clear that use of nuclear weapons would have devastated large swaths of Anatolia and Thrace, regardless of how quickly NATO responded to a Soviet first strike.

Aaron Stein is a PhD candidate at King’s College, London, an Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, and a research associate at the Center for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies, an independent think tank in Istanbul.

Notes

[1] “Transmission of the exchange of notes regarding the entry into force of Agreement for the Cooperation on the uses of Atomic Energy for Mutual Defense Purposes,” File no: 611.8297/7-2959, July 29, 1959, General Records of the Department of State, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), RG 59, Box 2553; Memorandum From Secretary of State Herter to Eisenhower, Eisenhower Library, Whitman File, Dulles-Herter Series, Secret, September 16, 1959, in US Department of State, Glenn W. LaFantasie, ed., Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960. Eastern Europe; Finland; Greece; Turkey, Volume X, Part 2, US Government Printing Office, 1958-1960, pp. 812-13.

[2] Lyndon B. Johnson and Ismet Inonu, “President Johnson and Prime Minister Inonu: Correspondence between President Johnson and Prime Minister Inonu, June 1964, as released by the White House, January 15, 1966,” reproduced in Middle East Journal 20 (Summer 1966), pp. 386-93; “Turkish Concern about U.S. Emphasis on Conventional Forces,” NARA, Cuban Missile Crisis Revisited, CU00179, Secret, Cable, Excised Copy, 001823, May 28, 1961, published in the Digital National Security Archive.

[3] “Turkish Position with regard to Trading Jupiters for Soviet Missiles in Cuba,” NARA, Cuban Missile Crisis, CC01328, Secret, Cable Paris, Corrected Copy, Polto 506, October 25, 1962, published in the Digital National Security Archive.

[4] “NATO Nuclear Planning Group, What Happened at Ankara,” NARA, RG 59, Central Foreign Policy Files, Box 1597, DEF 12 NATO, Paris 4422, September 30, 1967, Department of State, Telegram, General Records of the Department of State, NARA.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “NATO Nuclear Planning,” NARA, US Nuclear History, NH01023, Secret, Memorandum, January 10, 1967, published in the Digital National Security Archive.

[7] “Status report on the views of various countries consulted about the proposed nonproliferation treaty. These countries include: Belgium; Canada; Denmark; West Germany; France; Greece; Iceland; Italy; Japan; Luxembourg; the Netherlands; Norway; Portugal; Turkey; the United Kingdom,” Memorandum, Department of State, Secret, February 12, 1967. Date declassified: April 14, 1999, Declassified Documents Reference System (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014).

[8] “National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski is provided with the following information: Greek President Konstantinos Tsatsos’ opinion that the government of Turkey is not yet ready to negotiate a Cyprus peace settlement with Greece; Turkey’s position toward the nuclear nonproliferation treaty (NPT),” Memorandum, White House, Top Secret, December 9, 1977. Date declassified: February 01, 2005, Declassified Documents Reference System (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014).

[9] “NATO Nuclear Planning Group, What Happened at Ankara.”

[10] “Proceedings of the Tactical Nuclear Weapons Symposium, Held at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory of the University of California, Los Alamos, New Mexico, LA-4350-NM, Redacted Copy, held on 3-5 September 1969,” NARA.

[11] Melvyn P. Leffler, “Strategy, Diplomacy, and the Cold War: The United States, Turkey, and NATO, 1945-1952,” Journal of American History 71 (March 1985), pp. 807-25.